It is in giving that we receive.

I have just returned home from Burundi where I encountered a rather strange Belgian woman working for a local charity. We met at a health centre high in the hills south of Bujumbura, hemmed in by steep terraced slopes dotted with tin-roofed dwellings and lonely patches of trees. I extended my hand and greeted her in my best schoolboy French: ‘Bonjour. Je m’appelle Pete.’ She took my hand in a limp, damp handshake without uttering a word. The nun in charge of the health centre welcomed us all and explained the challenges they faced concerning inadequate water supplies, her flowing white habit flapping in the wind. A schoolgirl of 10 or 11 described her daily routine of walking a round trip of 4 kilometres to collect water, unaware of the incongruity of Justin Bieber smirking up from her soiled t-shirt. The nameless Belgian was a tall, broad women who seemed as uncomfortable in her frame as she was with other people. She listened to the conversations unsmiling, showing no reaction, all the time clutching a large plastic bag to her chest. Once inside the health centre she began to surreptitiously extract items from the bag and hand them one-by-one to the nun: several pairs of plastic slippers; some bandages; a packet of pills. The nun received them graciously, expressing her gratitude.

Before leaving, the woman approached the huddle of children outside the health centre to hand them some sweets. They jumped up and down laughing and screaming, trying to grab the precious parcels of pleasure. At once, the woman’s face lit up – as if someone had flicked a switch. She ran to the vehicle to fetch her camera, all the time beaming. She returned, her smile wider than ever, transformed: almost reborn. Although I’m sure that the gifts were genuinely appreciated, I couldn’t help wondering who had received more. The entire contents of the bag could not have cost her more than $20.

This experience reminded me of another encounter a few years ago with an American school teacher in South Africa. We happened to be visiting a rural school in Guateng at the same time and she was there with various hand-outs for the children: Kansas City baseball caps, t-shirts and sweets. She ran around the schoolyard with the children, frenzied, screaming, so happy she was out of control, as if high on drugs or alcohol. She then read letters from schoolchildren in Missouri (or somewhere equally parochial) sending their best wishes and hoping their African counterparts would like their gifts. The South African children then read their own letters expressing thanks to those far-off benefactors, no doubt busy on their PlayStations and iPads as those humble children spoke their heartfelt words. I couldn’t help but feel uneasy. Why should a child in Africa feel the need to be grateful to a child in the US or the UK or Japan? Is this not as much about power as trade barriers and wars for oil? And who is the real beneficiary (a word I detest in development language) here? It seems to me that these charitable souls are receiving far more than they’re giving. That’s not to say that what they are doing is necessarily wrong but we should disabuse ourselves of the notion that it is only one party doing the giving.

The Challenge

The day after encountering the enigmatic Belgian I found myself in an IDP (internally displaced person) camp surrounded by 20 or 30 children, all trying to hold hands with, or feel the skin of, the strange Muzungu (‘white man’ in Kiswahili). Among them was a young girl who refused to let go of my hand and bounced up and down beaming at me, seeming oblivious to the bigger children jostling for space around her. She must have been about 3 years old and yet she was shorter than my own son who is not yet 18 months. Burundi is rated worst on the Global Food Security Index and has one of the highest stunting rates in the world, with over 50% of children under five being stunted (low height for age) as a result of malnutrition.

The people in the camp were accommodated there when their homes were destroyed by floods and landslides in February this year. They were living in basic tents provided by aid agencies. I pulled aside the flap of one tent and peered inside. There was nothing except a pile of blankets and a few items of clothing: no possessions; no gadgets; no toys. Most of the camp residents were reluctant to go home. Why should they, when they had no house; no land; no hope? Aid agencies provide essential services in the camp such as shelter, water, sanitation and food for the under-fives, but what can charity do to improve their lives in the long term? Not a lot, perhaps.

I don’t believe in charity.

In general, I don’t believe in charity. It creates dependency and obligation and is built on unequal power relationships. That might strange coming from someone who has worked in international development and humanitarian relief, in one capacity or another, for 20 odd years (some of them very odd!). There are two exceptions, however. The first is in an emergency situation, such as the camp described above, following a flood, earthquake or conflict. I have worked for two charities – Médecins Sans Frontières and Oxfam – and in both instances I worked in emergency settings, providing water and sanitation to refugees or populations affected by disasters.

The second exception to my ‘I don’t believe in charity’ rule is more complex. This is where services which could, or should, be provided by the government or society (although of course there is no such thing according to Margaret Thatcher) are not and charities fill the gap. This happens in developed countries as well as less-developed ones. For example, regional air ambulance services and the Royal National Lifeboat Institution in the UK are registered charities. Although even here it could be argued that Government should provide these services, for me, the critical issue is when the services that should be provided are the most basic: water, sanitation, education and healthcare. Supporters of charities will no doubt argue: ‘But governments are not providing these services so we have to!’ This may be true in some cases but governments definitely should be providing them and charity may even prevent them from doing so, as it allows them to abrogate responsibility to someone else.

Charitable foundations

Of course, the current big thing in the charity world is ‘The Foundation’. There is now a plethora of foundations established by corporations, public figures and celebrities to help those less fortunate than themselves. All noble acts no doubt. But while I’m sure that all these businesses and individuals are genuine in their desire to help others (after all, it makes us feel good doesn’t it?) and they may even do some good for some people, one can’t help but wonder whether there’s often a bit too much ego involved and if it’s more about PR than anything else. Individual billionaires and multi-millionaires collectively commit billions of dollars every year to charitable foundations for good causes, including support to the poorest countries in the world. ‘This is good news, surely?’ I hear you protest. Well, yes it is. But then again, when you have several billion dollars a few billion more or less probably doesn’t make a whole lot of difference. The key question here is: why do individuals and corporations have so much more money than entire countries in first place? (The 85 richest people in the world have as much wealth as the 3.5 billion poorest.) And what makes rich people more qualified to make development decisions than governments, development agencies or communities themselves?

Warren Buffett, once the richest man on the world and still in the top four, is arguably the biggest giver to charity, having pledged more than $30 billion to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation alone (kudos to Mr. Buffett that he decided to give much of his wealth to a foundation other than his own). How did he make his money? By moving money around. Some will argue (and have to me) that he has lent money to business ventures that have developed innovative technologies, some of which have saved lives. Perhaps. But the fact is that he has made his vast fortune by moving money here and then there, and here and then there, without directly producing anything tangibly useful to society (which I do believe exists, contrary to Thatcher’s claim). A highly intelligent man, no doubt; but in making his money has he really worked so much harder or contributed more to society than the subsistence farmer or coal miner who toils day-in day-out for so little reward? This is no criticism of him as an individual. He appears to be a modest man and is clearly committed to helping those less fortunate than himself, to the extent that he has stated that his children will not inherit a significant proportion of his wealth, which will go to charity instead. It is, however, a criticism of the system that allowed him to amass the wealth he has.

The Solution

The only true solution is a more equitable and just world built on a more equitable and just economic system. Note that I say ‘more’ equitable and just. I am not so naive as to believe we will all have exactly the same opportunities and same assets. Even communism failed on that one. But I am convinced that we can have a much more equitable state of affairs. This means true fair trade (not just a stamp on a packet of tea) whereby a fair price is paid for raw materials, which are – sometimes literally – the lungs of our planet. It means more respect and more value for natural resources, less materialism and less waste (the millions of plastic bottles discarded every day are sought after possessions in rural Burundi). It also means effective taxation and wealth distribution. The profit incentive for businesses need not be removed completely but social, ethical and environmental factors must come first, and taxes should meet all basic requirements for all citizens. The priority should be economic equity (not equality) rather than economic growth. For this to work, true accountability of leaders is also needed; not just through the ballot box, which has its own limitations, but through international mechanisms to ensure that states deliver basic social services. The International Criminal Court (ICC) should not just focus on war crimes but on economic crimes (such as those of leaders who fill their pockets while their compatriots struggle in extreme poverty) which can be just as horrific and last far longer.

Unless we have sweeping economic (and political) reform, what hope is there for that little girl in the IDP camp? Can charity enable her to hope for similar opportunities as I hope for my own son? And yet, I believe wholeheartedly that she should. This will mean ‘sacrifice’ for my son, but only in terms of less possessions, less consumerism and less extravagance. And I have no doubt that he would agree happily to this if given the facts young enough and sensitized to the destructive power of commercial materialism and corporate power. It is the fear of loss that maintains the status quo.

Charities will continue to do their work, as will international development agencies, but simultaneously we must go beyond this and push for revolution of the global economic system and power dynamics. With new information technologies and an increasing disconnect between real people and the established powers (corporate and governmental), the future must belong to the crowds. Relying on charity is like placing a band aid on a severed limb; it may stem the flow here and there, but we remain incomplete, lacking our essential humanity.

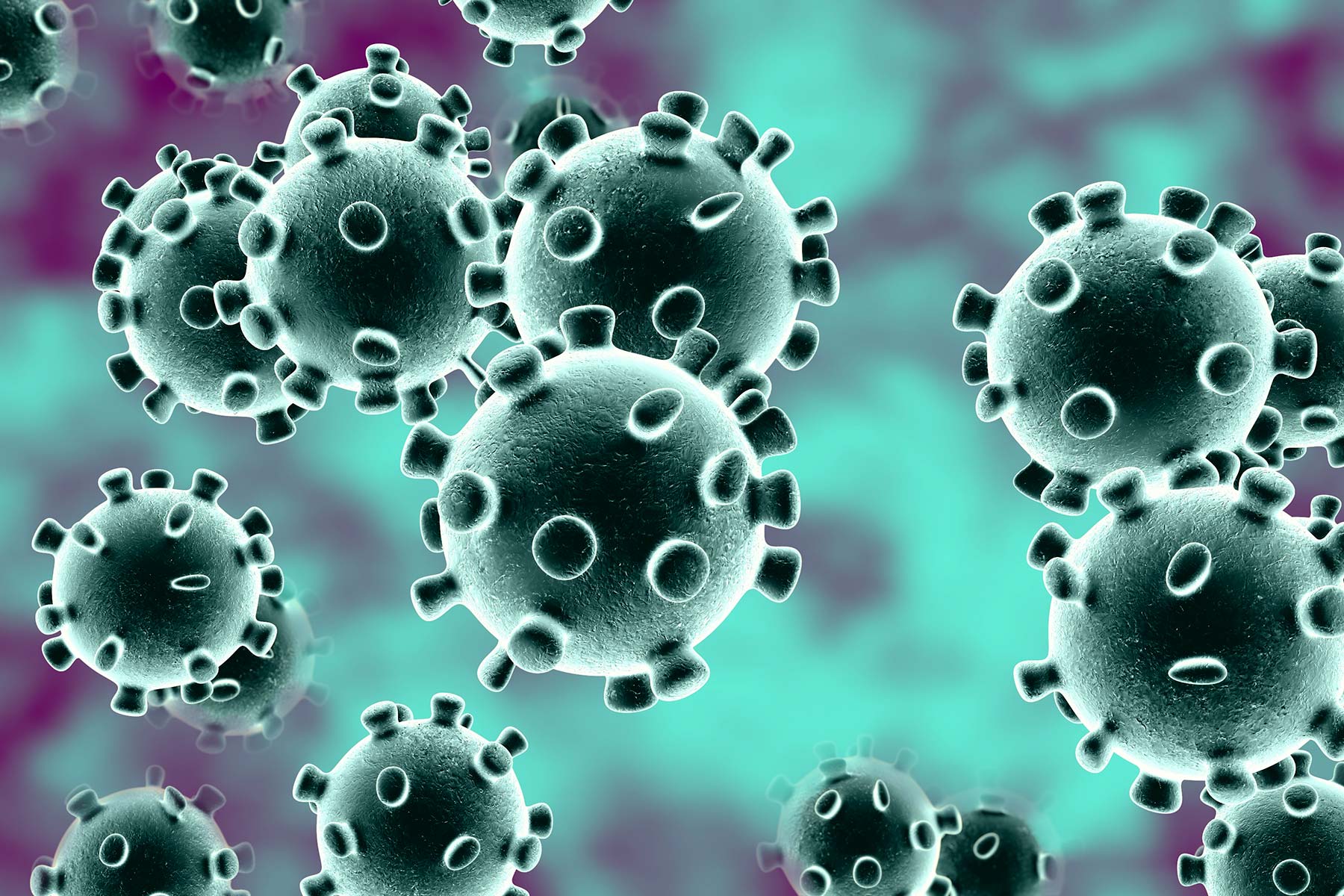

In just a few weeks, Coronavirus has managed to achieve what climate change protesters have failed to in years: air travel has been cut drastically; pollution-belching industries in China have closed; fewer cars are on the roads; no one is travelling to sporting and entertainment events; far less people are going out to restaurants and bars.

In just a few weeks, Coronavirus has managed to achieve what climate change protesters have failed to in years: air travel has been cut drastically; pollution-belching industries in China have closed; fewer cars are on the roads; no one is travelling to sporting and entertainment events; far less people are going out to restaurants and bars.